rooted in rock fungus weaves bumpy body inside, algae farms sunlight

Winter bleaches the high desert of color; even the evergreen needles of the piñon pines and twisted junipers fade when cold freezes the water they need to photosynthesize. I search out lichens, which stay active by “sipping” water from snow, fog and even nighttime hoarfrost as the sun melts the crystals into liquid.

Today, I am fan-girling lichens. Because in these bitterly cold days when a blanket of new snow covers the ground, the high desert landscape I walk is almost monochrome, a tapestry of light and shadow. Only lichens provide splashes of color. For their vivid toughness—and the sheer weirdness of the lives, I am grateful.

Lichens color outside the lines

Lichens are fascinating creatures in part because they fit in none of our taxonomic boxes. Lichens are neither plant nor animal: a lichen is composite organism created by a fungus who weaves a body (the thallus) within which lives a microscopic photosynthesizing partner (or two) who uses sunlight to make the organism’s food. In a sense, a lichen is a miniature ecosystem, but I am going to call them composite organisms for simplicity.

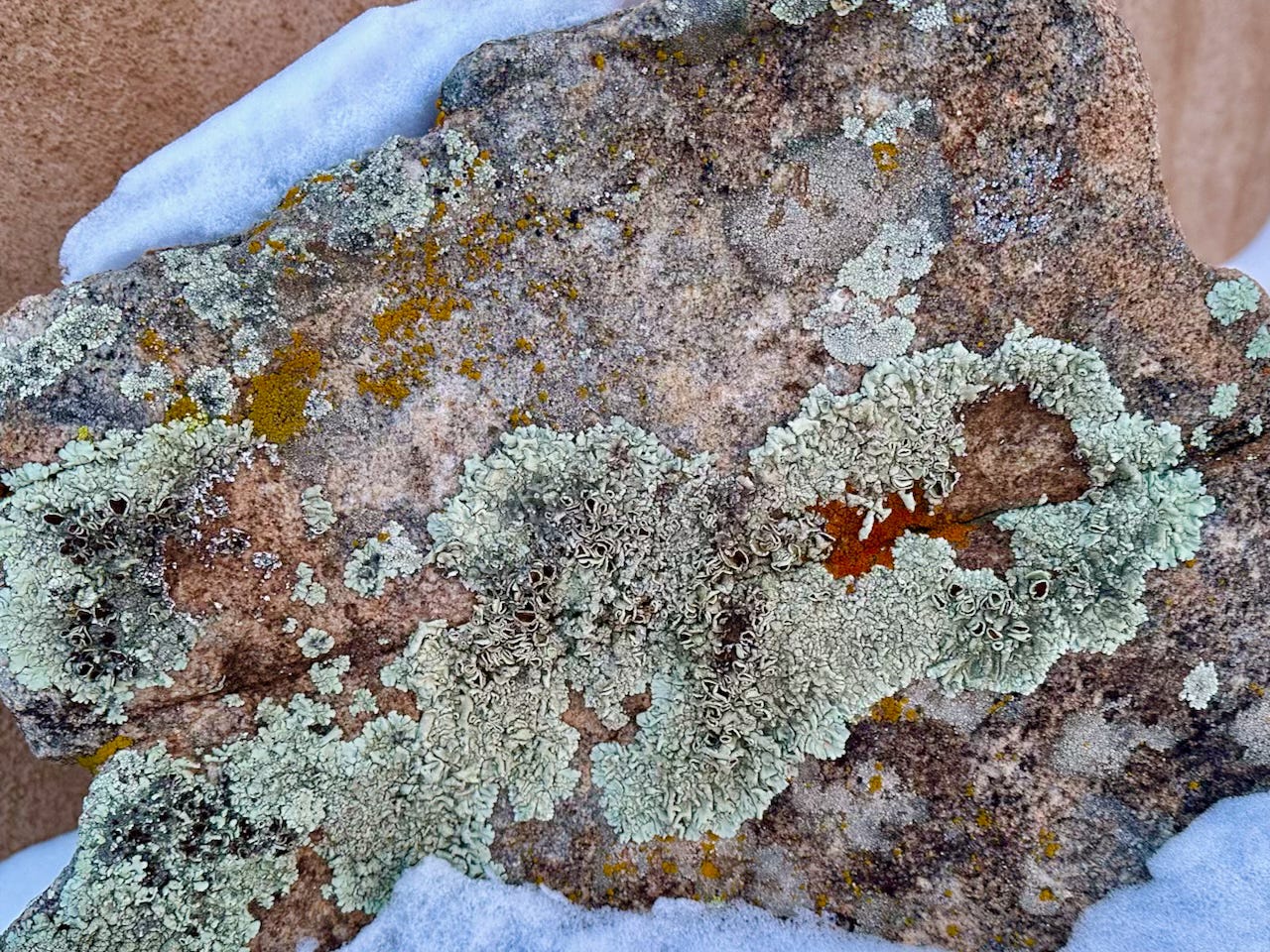

The photosynthesizing partner—usually an alga, sometimes a cyanobacteria, and less often, both—is what colors the composite organism. The pigments these single-celled photosynthesizers make to capture the energy in sunlight range from soft greens to acid orange and chrome yellow, and also black and gray.

Those pigments are brightest after rain, snow or fog wets the thallus (or water poured from a water bottle, as I have demonstrated on many nature walks), making the fungal threads transparent and allowing sunlight to wake the algae or cyanobacteria within. The photosynthesizing beings then go to work splitting carbon dioxide into oxygen and carbon, and using the carbon plus minerals harvested from dust in the air to make food for the composite organism.

What happens when a fungus and an algae take a lichen?

(Sorry, I couldn’t resist the pun.) Lichens come in a variety of forms, including crustose, foliose, and fruticose. Crustose lichens adhere tightly to their substrate and cannot be easily pried off. Foliose lichens look leafy, and have a lower layer that is darker than the upper layer. Fruticose lichens look like tiny, multi-stemmed shrubs, and are the ones that are often seen hanging from tree branches in mountain evergreen forests. (Spanish moss of live oak woods in the South is not a lichen, however; it is a plant related to pineapples.)

Can you identify the different forms in the gallery above? Look again at the photo of the lichens on the rock at the top of the post. How many different lichens can you see in the photo? (Clue: look for the different colors and forms.)

Lichens are complicated and very, very long-lived

There is so much more to say about lichens—in some cases, the fungus may actually capture the photosynthetic partner, making the composite organism a parasitic relationship rather than a mutually beneficial one.

Lichen reproduction is complicated, since both partners’ cells must be contained in the spores the fungus releases. Some lichens contain yeasts as well, which may be key to the fungus producing the characteristic lichen body woven around the alga or cyanobacteria. And their slow growth and persistence gives them a place among earth’s longest-lived organisms—an arctic lichen has been dated at 8,600 years old!

I am grateful for lichens, for the splashes of color they provide in the winter landscape, for the wonder of their unusual partnership and lives, and for their example of resilience and creativity.

What do you like about lichens? Hit the comment button and let me know!

What I like are the things we don't know about lichens.

I'm lichen your essay on lichens, dear Susan. As a total non-scientist, I know virtually nothing about lichens. But you have definitely stirred my curiosity. I shall henceforth look at them in a whole new light, while not blocking their access to light, of course. Thank you so much for opening up this world for me.